The Press That Fought for a Language: Odia Literary Revolution in Colonial India

- Soumyaranjan Sahoo

- Nov 7, 2025

- 6 min read

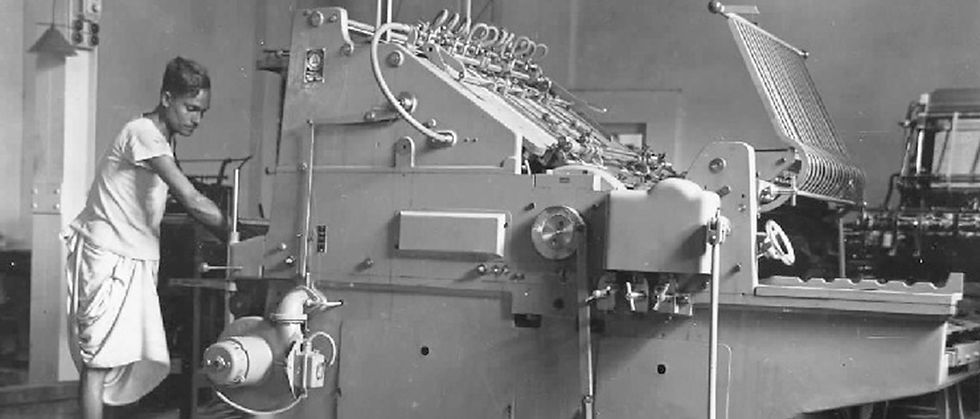

The Odia literary upsurge of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did not happen in isolation; it was inseparable from the arrival, spread, and creative appropriation of the printing press. Print technologies enabled a dispersed society to share a common language space, accelerated debates about identity and modernity, and gave Odia writers the tools to build a public sphere robust enough to withstand both colonial and regional pressures. From the first mission presses and Scriptures to secular newspapers, magazines, dictionaries, and encyclopedic projects, printing forged the infrastructure on which a recognizably “modern Odia” literature and political community could stand.

From mission type to a language public: the technological beginnings

Like elsewhere in India, print in Odisha initially rode on missionary enterprise. Serampore Mission Press produced the earliest Odia items (including a New Testament portion) as early as 1807, setting compositors, type, and orthographic conventions in motion. By 1837, the Baptists established the Cuttack (Orissa) Mission Press on Odia soil, making vernacular printing local and repeatable. Missionaries such as Charles Lacey and Amos Sutton compiled grammars, dictionaries, school texts, and biblical translations, providing printers with steady copy and readers with a regular supply of Odia prose. This corpus mattered less for its theology than for the fact that it stabilised fonts, page layouts, and a prose style that later secular editors could rework for literary and civic ends.

The Cuttack Mission Press was not a boutique outfit. Surviving reports show scale and range—hundreds of thousands of tracts, gospels, and “miscellaneous scriptures” were issued, which normalised Odia printed pages in town and mofussil alike. One detailed account speaks of 952,700 tracts (12–36 pages), 77,000 gospels, and over 31,000 other scriptural pieces—figures that indicate both production capacity and distribution networks into which later Odia editors and publishers could plug their secular wares.

Newsprint, nationalism, and literary modernity

The catalytic turn came when Odia elites domesticated this technology for civic and literary aims. Gourishankar Ray founded the Cuttack Printing Company (1866) and launched Utkala Deepika (4 August 1866), the first printed Odia newspaper—an organ that became both a literary platform and a pressure group for bringing Odia-speaking tracts under one administrative unit. The paper’s weekly rhythm created a new expectation of timely prose, editorials, serialised essays, and correspondence—habits that reshaped literary diction and public argument in Odia. The date of its first issue is still commemorated as Odia Journalism Day, underlining its canonical status in the language’s print memory.

Within three decades, the magazine Utkal Sahitya (1897), edited and published by Biswanath (Viswanath) Kar, widened the canvas. It ran essays on literature, science, economics, religion, and public affairs, demonstrating how a magazine could be the school of modern prose while inducting new readerships into multi-topic literacy. Surviving volumes and archival reconstructions show how Utkal Sahitya became a training ground for writers and a clearinghouse for new genres—literary criticism, scientific primers, and reflective prose—that now define Odia modernity.

Fakir Mohan, the printing entrepreneur, and the fight for Odia

If the press made modern Odia literature possible, writer-entrepreneurs made it inevitable. Fakir Mohan Senapati—now celebrated as the father of Odia nationalism and the pioneer of the modern Odia novel—did not merely write; he founded presses (Utkal Printing Company in 1865; Balasore Utkal Press in 1868), edited journals, and used the printed page to defend Odia’s distinctness against proposals to subsume it under Bengali in schools and administration.

His autobiography and contemporary records, together with state and scholarly retrospectives, document how his business of printing was inseparable from his literary and political mission. The press gave him speed, reach, and a professional base to nurture prose realism, satire, and a language of civic indignation that readers could recognise as their own.

Satyabadi, The Samaja, and the freedom decade

In the early twentieth century, the Satyabadi circle led by Gopabandhu Das turned printing into a mass pedagogy and nation-making device. Das launched the weekly The Samaja on 4 October 1919 from Satyabadi, using simple prose and relentless reportage to carry freedom-movement messages, public health notes, rural economy debates, and civic instruction into households.

The paper’s later shift to daily publication amplified its influence; even official speeches now archive the memory of how The Samaja enriched Odia letters and public life by democratizing access to print. The Satyabadi Press model—school, press, paper—showed how a vernacular ecosystem could be built by anchoring print to community institutions.

The dictionary as civilisation: Praharaj and the Nababharat tradition

If newspapers quickened the pulse, lexicography gave Odia a spine. Across the 1930s, lawyer-publisher Gopal Chandra Praharaj compiled and oversaw the printing of the seven-volume, ~9,500-page Purnachandra Odia Bhashakosha, a multilingual (Odia-English-Hindi-Bengali) dictionary-cum-encyclopedia listing ~185,000 entries with quotations, botanical and astronomical notes, and biographical capsules.

Scholars of print culture have underlined how this was not merely a reference book but a civilisational claim, executed through a long, technically demanding print project in Cuttack that rallied patrons, subscriptions, and press labour over a decade. Modern print histories and encyclopedic entries situate Praharaj’s project alongside Cuttack’s notable presses (e.g., Nababharat Press) that sustained ambitious book-length Odia projects in the interwar years.

A widening archipelago of presses and periodicals

By the fin-de-siècle, Odisha had multiple private presses beyond the missionary and pioneer firms: Cuttack Printing Company (1866), P.M. Company (Balasore, 1868), Dey Press (Balasore, 1873), Nisha Nesedhini Samaj Press (1875), Puri Printing Corporation (1890), Arundoya Press (1893), Roy Press (1894), Darpanraj Press (1899), Binod Press (Balasore, 1899), and Utkal Sahitya Press (Cuttack). This network enabled short-lived experiments and long-running successes; taken together, they document a society testing genres, readerships, and the economics of print—an ecology from which canonical authors and lasting institutions emerged.

What, precisely, did printing change?

First, print regularised Odia prose—its punctuation, paragraphing, and idiom—and expanded its registers from devotional to scientific and civic. Second, it created speed: weeklies and monthlies turned ideas into conversation, and conversation into mobilisation. Third, it gave Odia the archival depth of dictionaries, schoolbooks, periodicals, and bound volumes that could be reprinted, excerpted, and taught. Studies of media and nationalism underscore how nineteenth-century Odisha’s print sphere allowed a sense of “Odia” community to prefigure, and then participate in, Indian nationalism—showing why the defence of Odia as a distinct administrative-educational language succeeded.

Finally, the press professionalised literary labour: editors like Gourishankar Ray and Biswanath Kar built editorial pipelines; author-publishers like Fakir Mohan ran presses; teacher-publicists like Gopabandhu institutionalised school-press-paper ecosystems. This mix of craft, capital, and conviction explains the density of Odia periodicals and the self-confidence of Odia prose by the 1930s.

Why do their achievements deserve to be glorified?

The grounds for celebration are empirical. We have mission-press output statistics measuring hundreds of thousands of Odia items printed and circulated; exact launch dates of milestone publications (Utkala Deepika in 1866; The Samaja in 1919; Utkal Sahitya in 1897); the bibliographic bulk of a 9,500-page dictionary; and the documented proliferation of private presses across Cuttack, Balasore, and Puri within a generation. These figures demonstrate sustained capital investment, skilled compositing and typesetting in Odia, and a deepening market for Odia reading—conditions without which a literary “revolution” is only rhetoric.

The present landscape: From Collective Consciousness to Commercial Content

Today’s print ecosystem stands at a difficult crossroad. Legacy dailies such as The Samaja and Dharitri continue in print and digital editions, while the Government’s Directorate of Printing, Stationery & Publication and the State Textbook Bureau still handle large-run printing of gazettes, budgets, and textbooks—remnants of a system once built to educate and inform. Industry observers describe Odisha as a small but evolving print market with improvements in colour, pagination, and regional editions. Yet beneath this surface of modernisation lies a more uncomfortable truth.

The press that once united thinkers, editors, intellectuals, freedom fighters, and entrepreneurs around ethics and nation-building is no longer the same press. Where Odia printing once carried the moral weight of collective consciousness—where editors debated identity, argued for education, and defended language—the current ecosystem is caught in a cycle of commercial survival, advertisement dependency, and political patronage. The influence of capitalist models has turned several media houses across India, including Odisha, into revenue-driven corporations. The rising cost of newsprint, collapsing subscription culture, and the dominance of real-time digital media have forced many to chase what sells rather than what matters.

Digital adaptation is not the crisis; ethical erosion is.

News has become a commodity; truth, a negotiable product. If the early Odia press risked imprisonment to tell the truth, today’s press often risks irrelevance by refusing to. Sections of the industry increasingly serve the interests of whoever funds them—business houses, politicians, or PR narratives—while journalists struggle for job security, fair pay, and editorial independence.

In this fractured landscape, heritage actors attempt to preserve what remains—through archives, museums, and restoration of old presses—yet preservation without ethical revival risks turning a revolution into a relic. The Odia printing press once built a public; now the public must rebuild the press.

References:

Jatindra K. Nayak, “Print Culture in Odisha” (PrintWeek, 16 Apr 2021).

G. W. Shaw, “The Cuttack Mission Press and Early Oriya Printing” (British Library repository).

Sahapedia, “The History of the Printing Press in Odisha.”

Utkala Deepika (overview and first issue date).

Odia Bibhaba, dossiers on Utkal Sahitya and Utkal Dipika.

Archive.org facsimile: Utkal Sahitya Vol. 1 (1897).

Odisha Review essays on Fakir Mohan Senapati (2016) and press lists (2017).

The Samaja origins: PIB press note; Odisha Review profile.

Research on Odia identity and nineteenth-century print media.

Overview of Purnachandra Odia Bhashakosha.

PrintWeek features on Nababharat Press and Odisha print heritage.

Government and institutional print today: Directorate site; Textbook Bureau catalog.

Comments